WWI by 10 Magnum Photographers

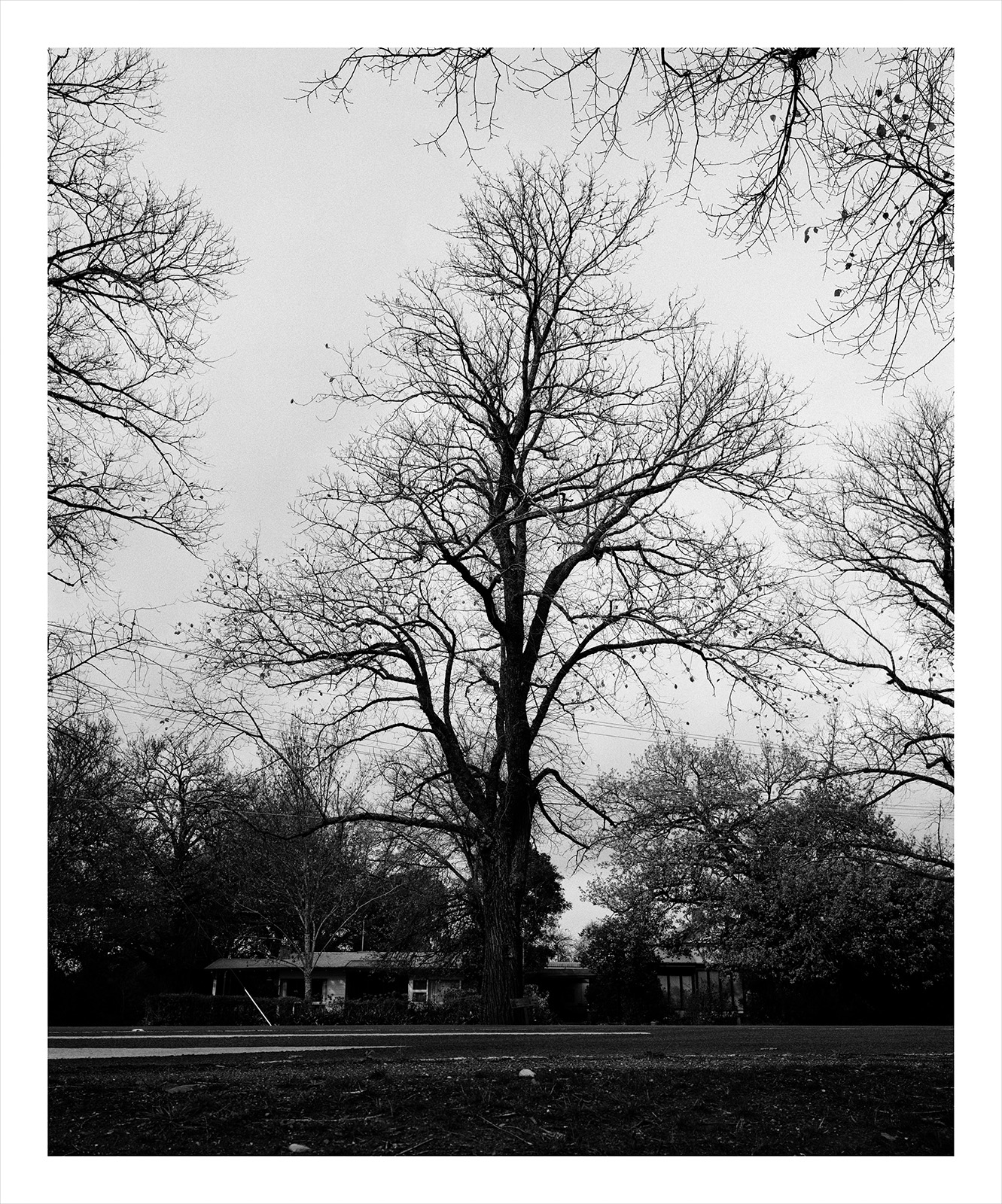

Alec Soth - Code Talkers Highway

Can we commemorate something that was never known? Alec Soth (1969) takes us with him to the state of Oklahoma, home to the choctaw native americans. In 1830s, the Choctaws were forced off their land and relocated to Oklahoma. By the early twentieth century, they had lost many of their tribal rights and were still not granted full citizenship, but many of them enlisted to serve in world war i nevertheless.

Alec Soth portrays the descendants of the nineteen choctaw indians who served as ‘code talkers’ in the us army in the first world war. these soldiers played a vital role in the final weeks of the conflict, transmitting messages in their own language instead of english. the germans listening in had no idea what they were hearing. the achievements of thesepatriotic native americans went largely unacknowledged. nowadays the area around the code talkers highway is extremely impoverished.

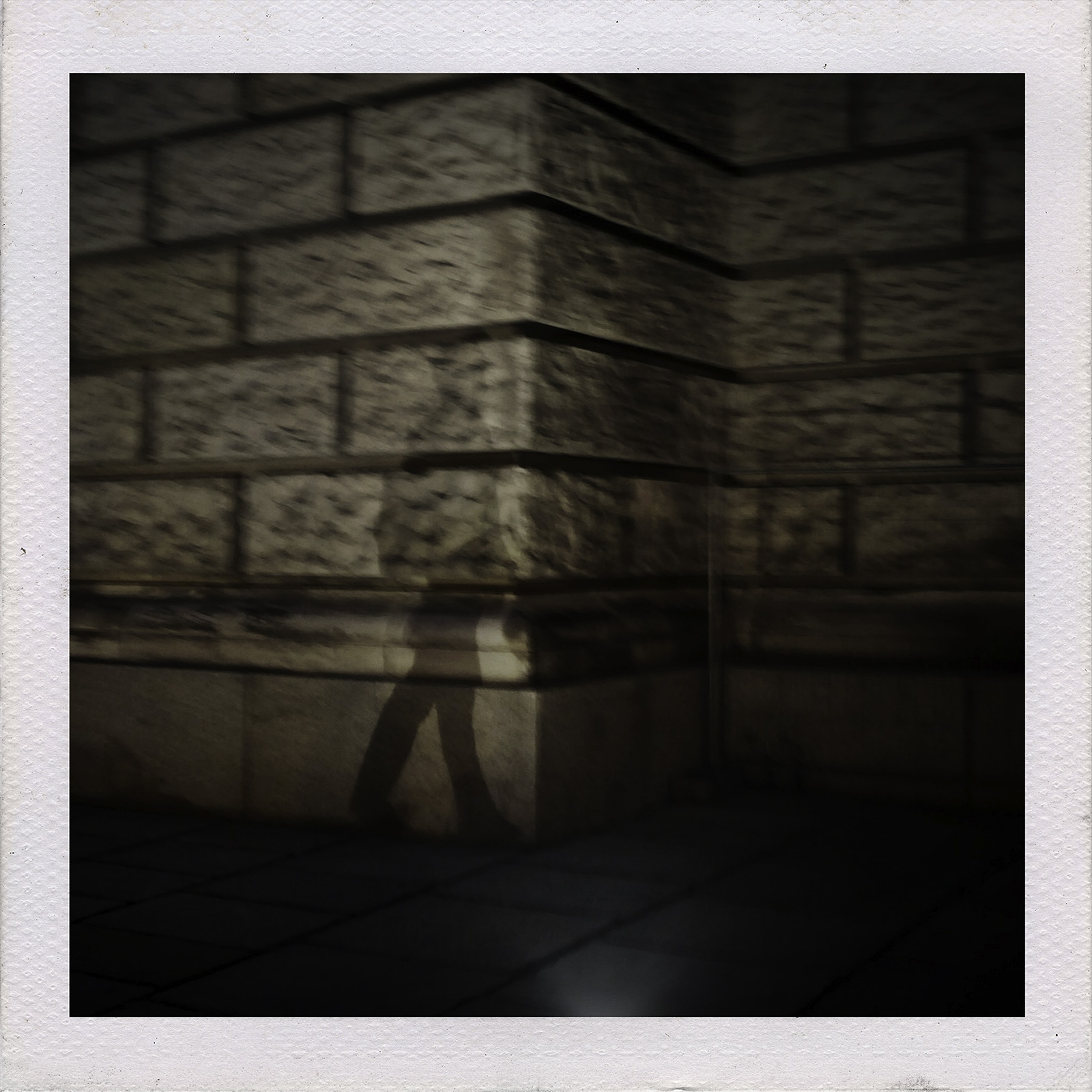

Mark Power - Peacehaven

The British photographer Mark Power (1959) worked in Peacehaven, a small town on the south coast of England. Founded in 1916 as part of the British government’s ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ campaign, it was hoped that this seaside Arcadia would become a place where traumatised war veterans could build new lives. Following the Battle of the Somme that same year, 40% of casualties were considered shell-shocked, resulting in concern about an epidemic of psychiatric disorders. Indeed, even ten years after the end of the war there were still 65,000 British veterans receiving treatment. ‘I tried to create an atmosphere of unease amongst the sleepy bungalows of the town, where a fleeting glimpse or an unexpected sound might spark nightmarish memories of a life best forgotten.’

Alex Majoli - Scenes

‘The moment people get near a camera, they start playing a role. Everyone does it, myself included.’ Alex Majoli (1971) is fascinated by the theatricality of real life. Rather than deconstructing it, though, he wants to enlarge it. He joins in the game, producing images that are deliberately filmic and theatrical. He spent time for this series with a group of local re-enactors in northern Italy, who restage historic battles. The pictures were shot in daylight, using a combination of underexposure and flash.

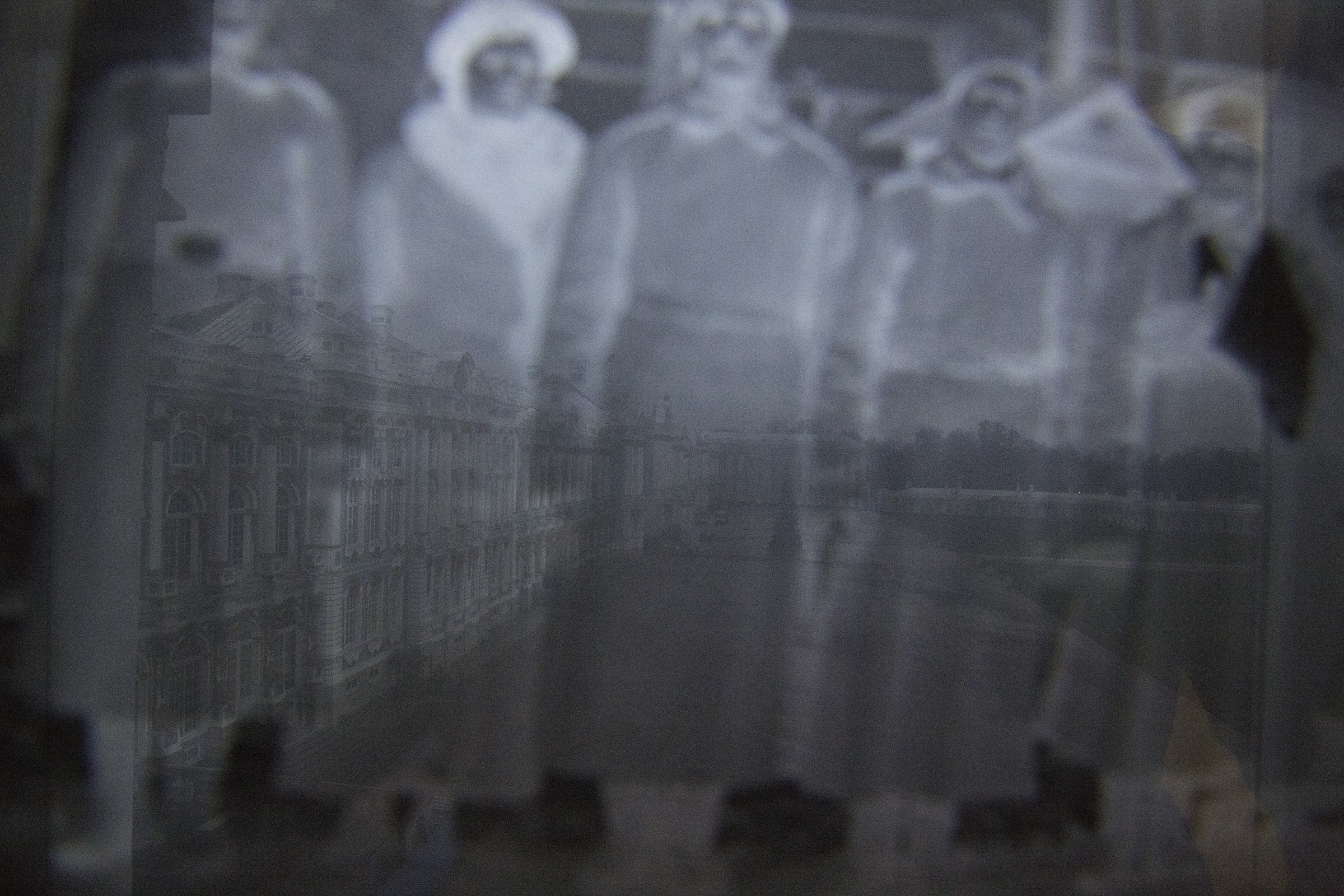

Gueorgui Pinkhassov - The Point of Origin

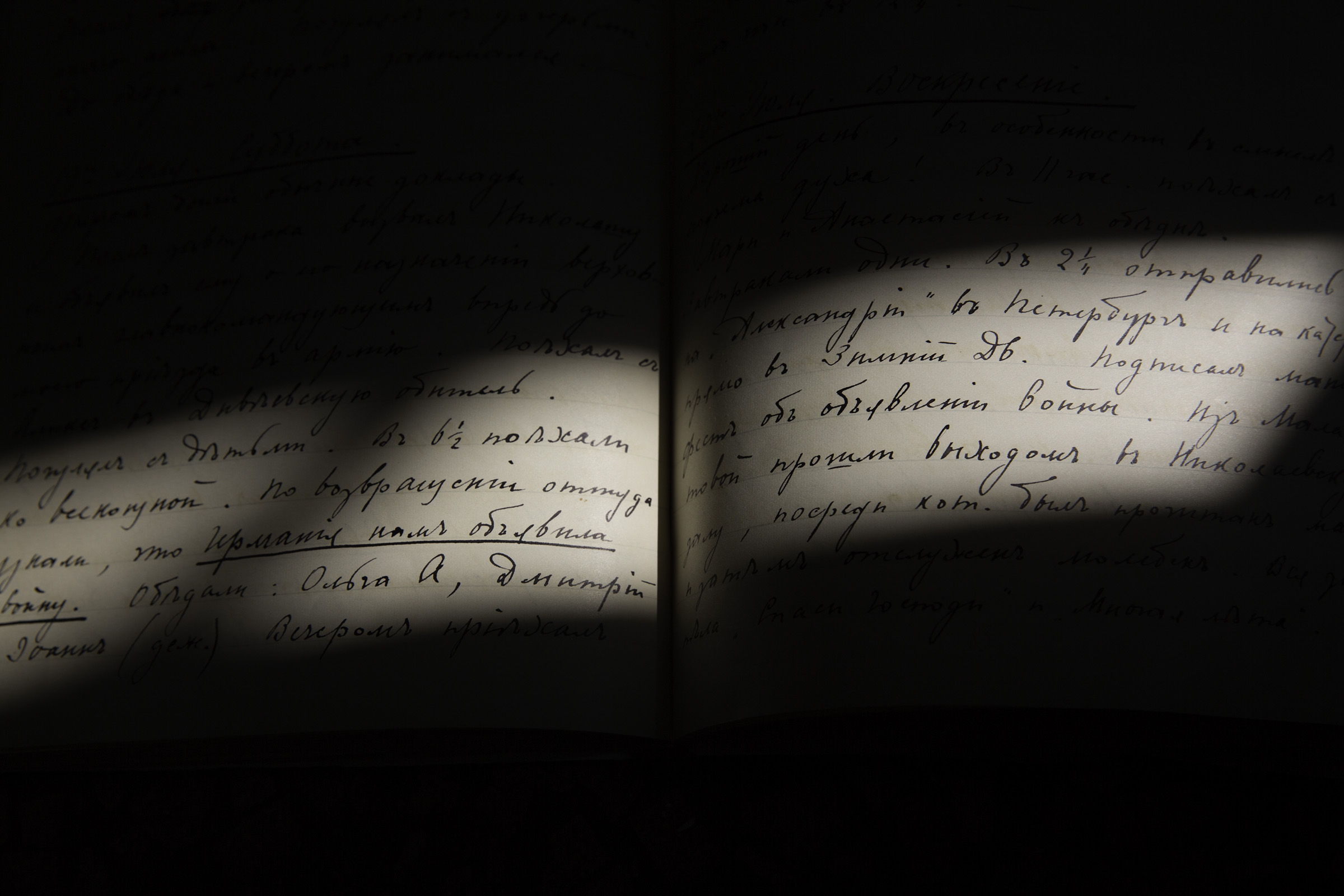

Rather than analysing the causes of war like a historian, Gueorgui Pinkhassov (1952) sought a visual image of its origins. He found it on page 161 of Tsar Nicholas II’s diary.

On July 19, 1914, amidst casual remarks about a walk and a lunch, the Tsar made his first entry about the beginning of the war.

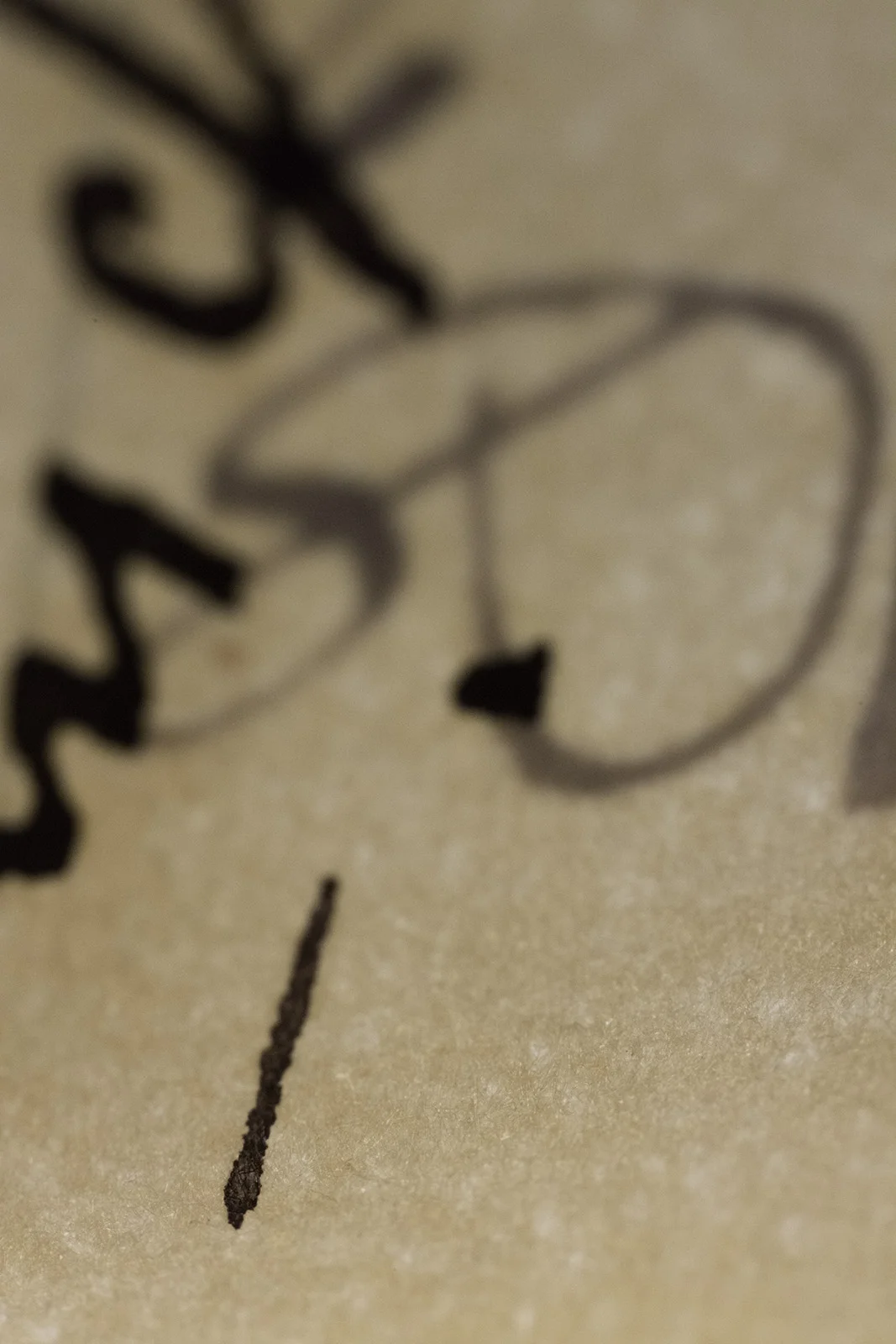

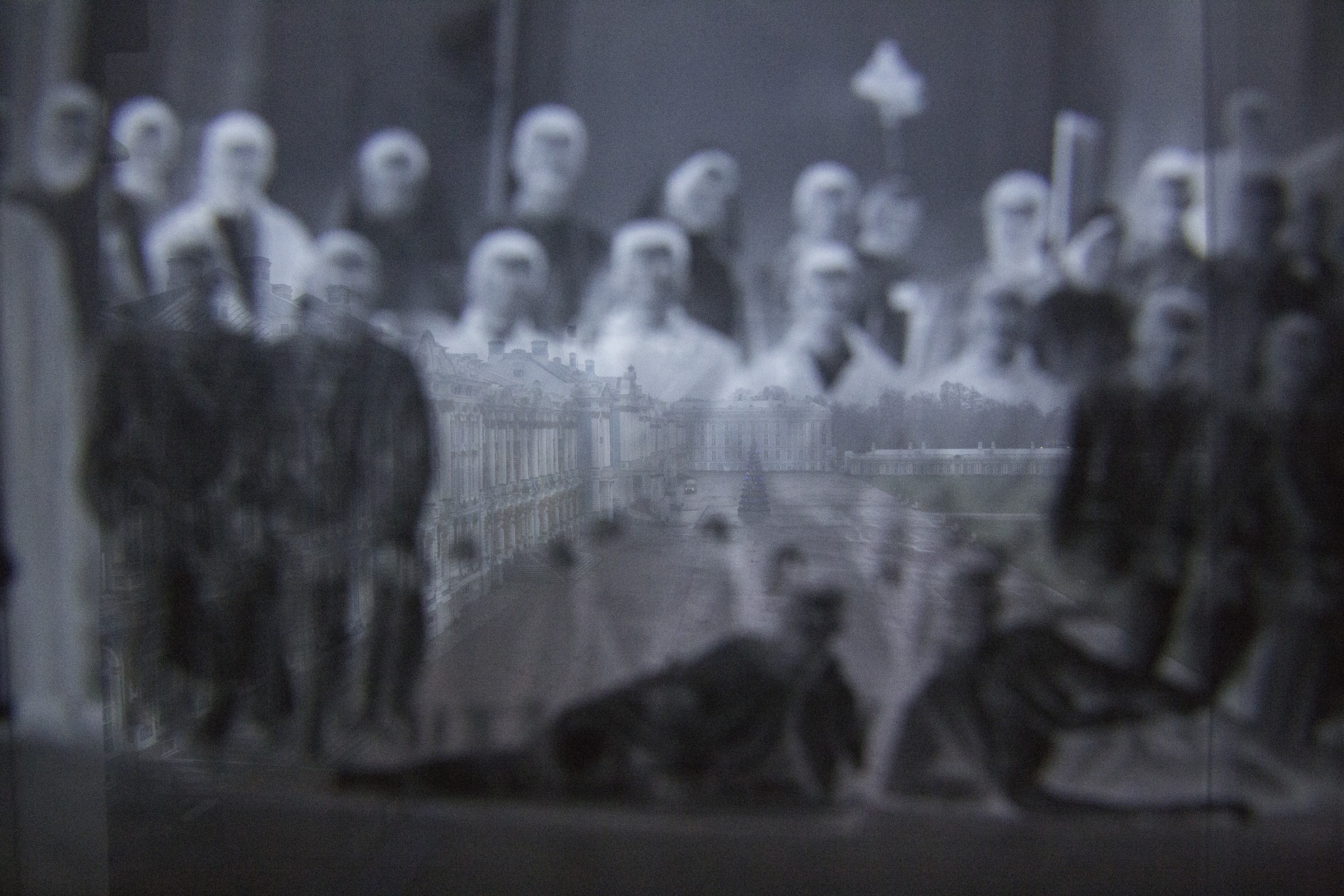

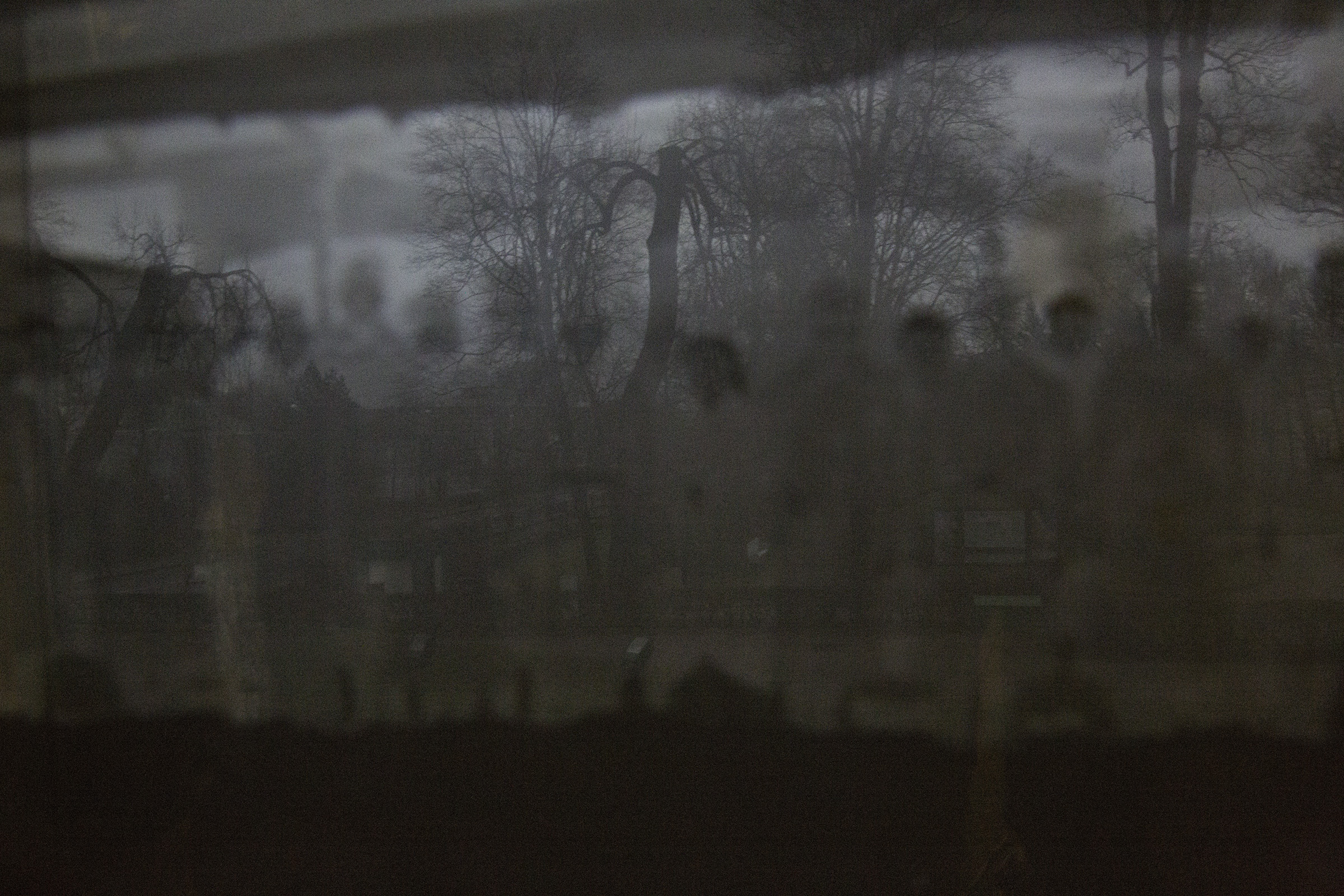

‘The word “war” is underlined, followed by a period. I looked at this point so closely that I could feel the breath of the paper and see the composition of the ink. I understood Malevich’s desire to reduce the world to a black square.’ Pinkhassov likewise held original negatives from the tsar’s family in front of his camera when visiting the palace: faces and façades merge in a single haunting overlay of past and present.

July 19. Saturday.

In the morning, there were the usual reports.

After breakfast called Nikolasha and told him of his appointment as Commander-in-Chief until I rejoin the army. Travelled with Alix to Diveevo convent.

Took a walk with the children. At 6½ went to the night service. Upon returning therefrom, learned that Germany has declared war on us. Had dinner: Olga A[lexandrova], Dmitry and John (duty off.). Eng. Ambassador Buchanan arrived in the evening with a telegram from Georgie. Spent a long time composing a response with him. Then also saw Nikolasha and Fredericks. Drank tea at 12 1/4.

Chien-Chi Chang - Echoes from the Dual Monarchy

‘We are children of the past. Commemoration is the only form of immortality we can achieve.’ Chien-Chi Chang (1961) cannot remember who wrote that quote, but he muses about it quite often. Born in Taiwan but living in Austria, he went in search of echoes of the once mighty austro-hungarian empire, which fell apart during the war.

He found parades, monuments, graveyards and even descendants of the Habsburg emperor. What made the most powerful impression on him, however, was Thalerhof — an important first world war concentration camp, now located near Graz airport.

Thalerhof by Chien-Chi Chang

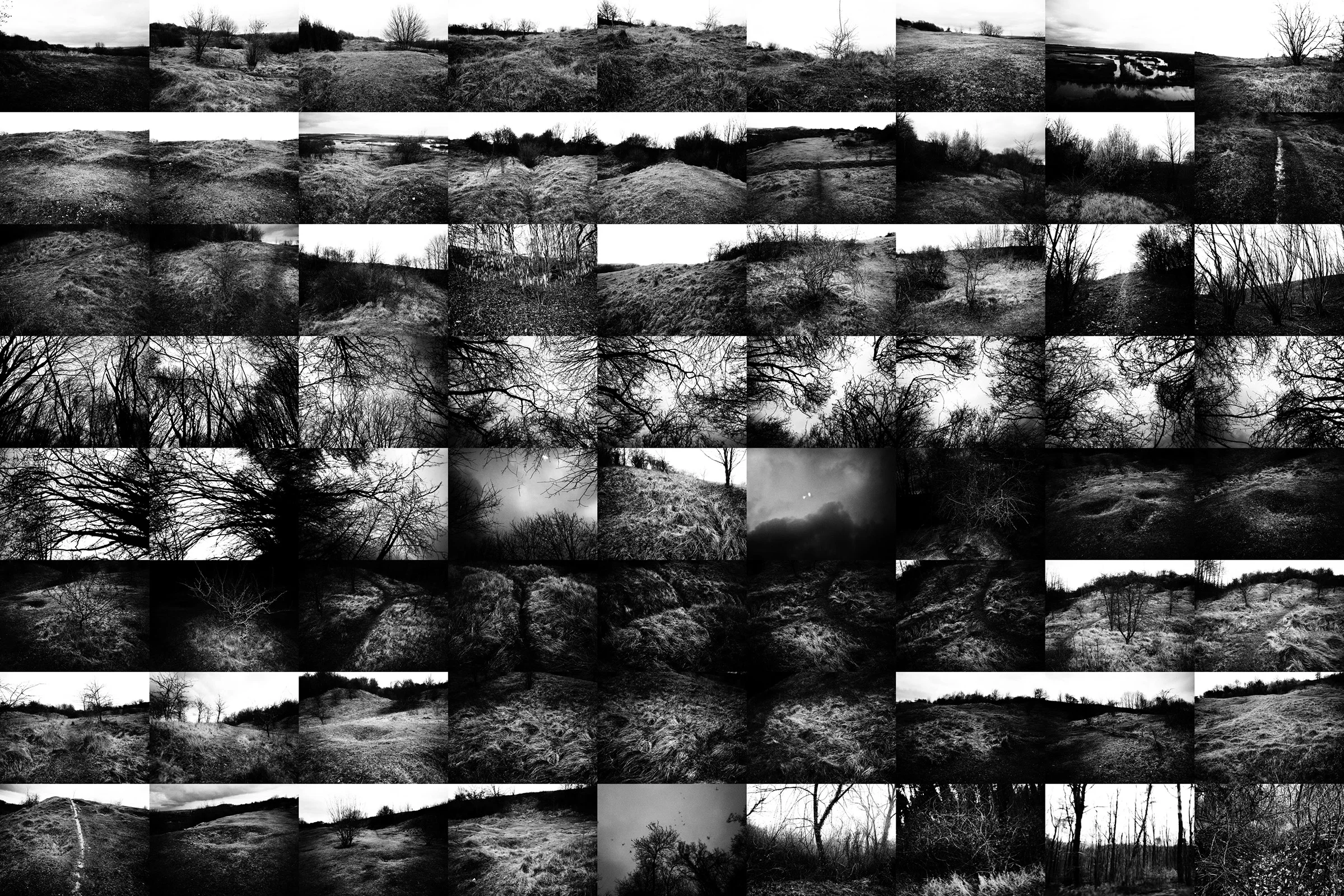

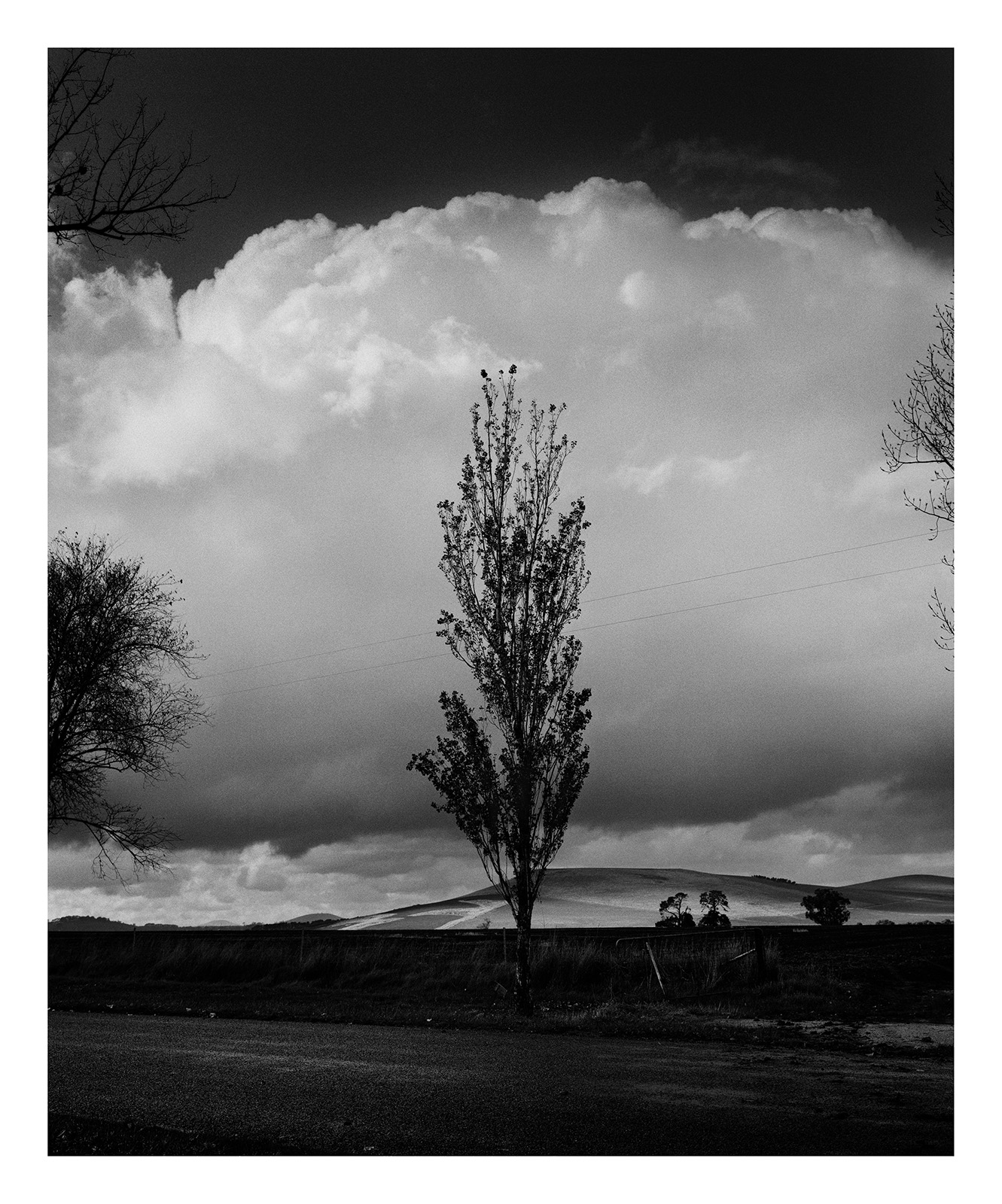

Antoine D'Agata - Notes pour un mémorial

The French photographer Antoine D'Agata (1961) retraced the french front from the Belgian border to Switzerland. After travelling the full 800 kilometres, he wrote: ‘there is nothing left to document. everything that hasn’t disappeared or become inaccessible has already been catalogued or put in a museum.’ He opted for a subjective, obsessive landscape photography. ‘it turned into a road movie with hundreds of trees, a memorial for those who refused, but above all a sense of failure: the impossibility a hundred years on of understanding what that war, that extraordinary horror, must have been like.’

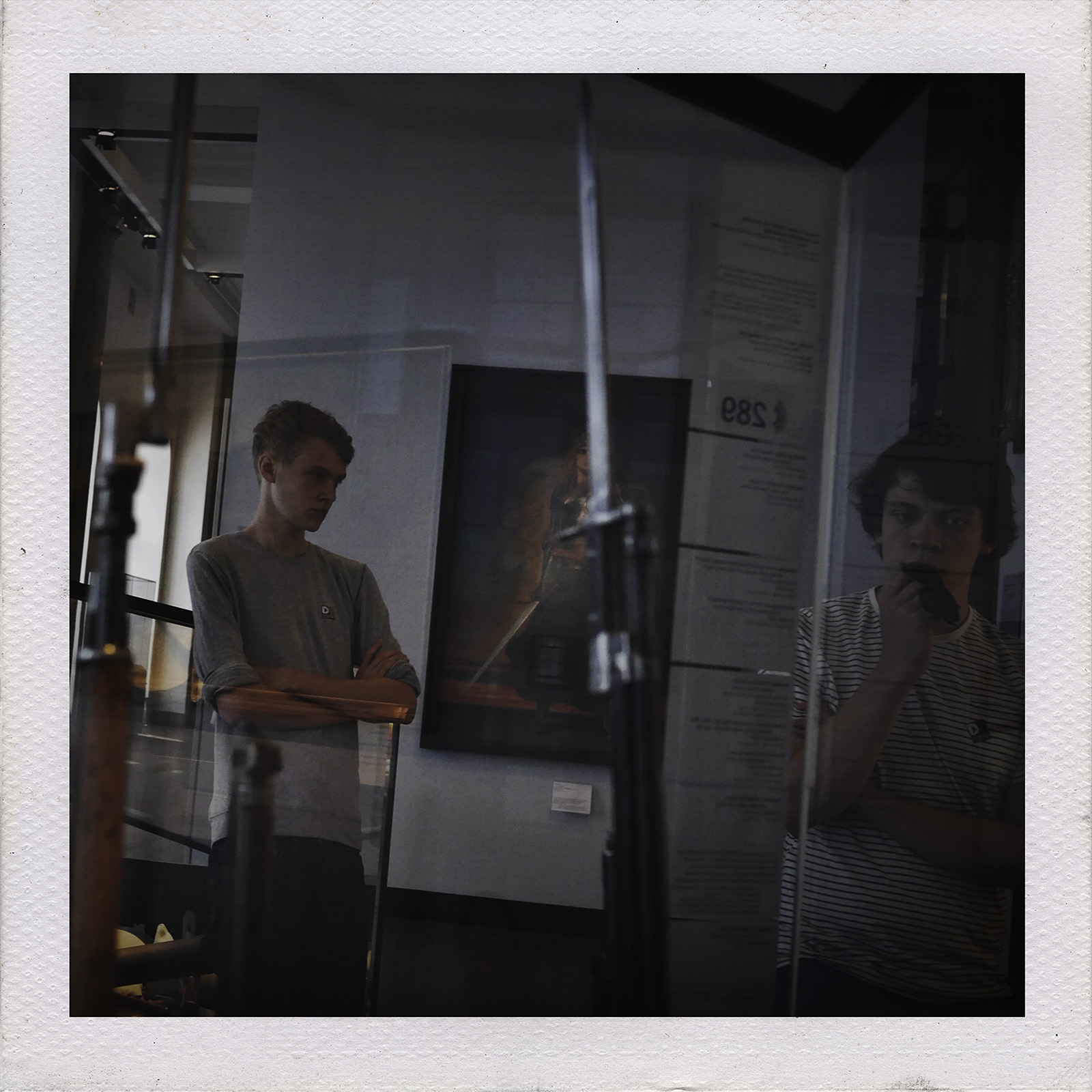

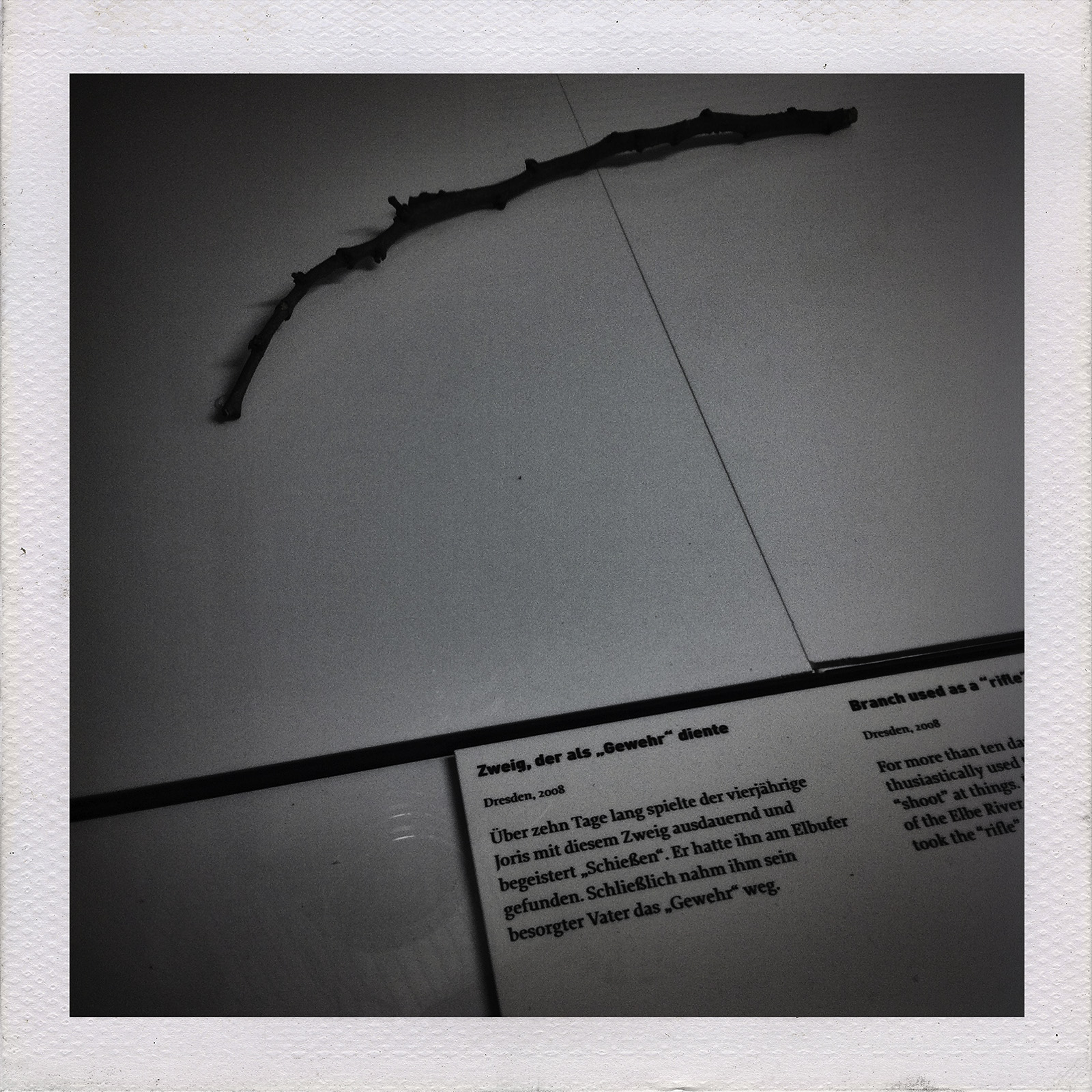

Thomas Dworzak - Kriegsspiele

‘I grew up in Germany, so my knowledge of the first world war was totally over-shadowed by that of the second,’ Thomas Dworzak (1972) says. ‘we were too burdened by our historical sense of guilt to play war games as children.’ but can ‘restaging’ also be a form of remembrance? Dworzak travelled with a small group of Bavarian re-enactors to Passendale (Passchendaele), Ilmenau and Strasbourg, where he witnessed ‘a very European movement’. online, meanwhile, he found a cascade of images that give an insight into how people today relate to the great war.

Carl De Keyzer - Ypres

An aerial photo showing the ruins of ypres blanketed in snow prompted Carl De Keyzer (1958) to return to black and white for the first time in fifteen years. he spent numerous winter nights photographing the reconstructed city. ‘The past seems frozen there,’ he says, ‘as if under a bell-jar.’ Beyond the city, the wider region offers a messier form of remembrance alongside all the official monuments. Futility galore. ‘What i want most of all is to show the impossibility of remembrance.’

Nikos Economopoulos - Balkan Beginnings

Nikos Economopoulos (1953) returned to where it all began: the balkans. In Bosnia, he photographed the weapon that fired the first shot of the war, and in Macedonia, a cemetery for over a thousand Serbian soldiers. InTturkey he visited the site where the battle of Gallipoli is commemorated. He links these images seamlessly with scenes from athens today: ‘The same portents. Fear and despair. Poverty and insecurity ... let it be a warning.’

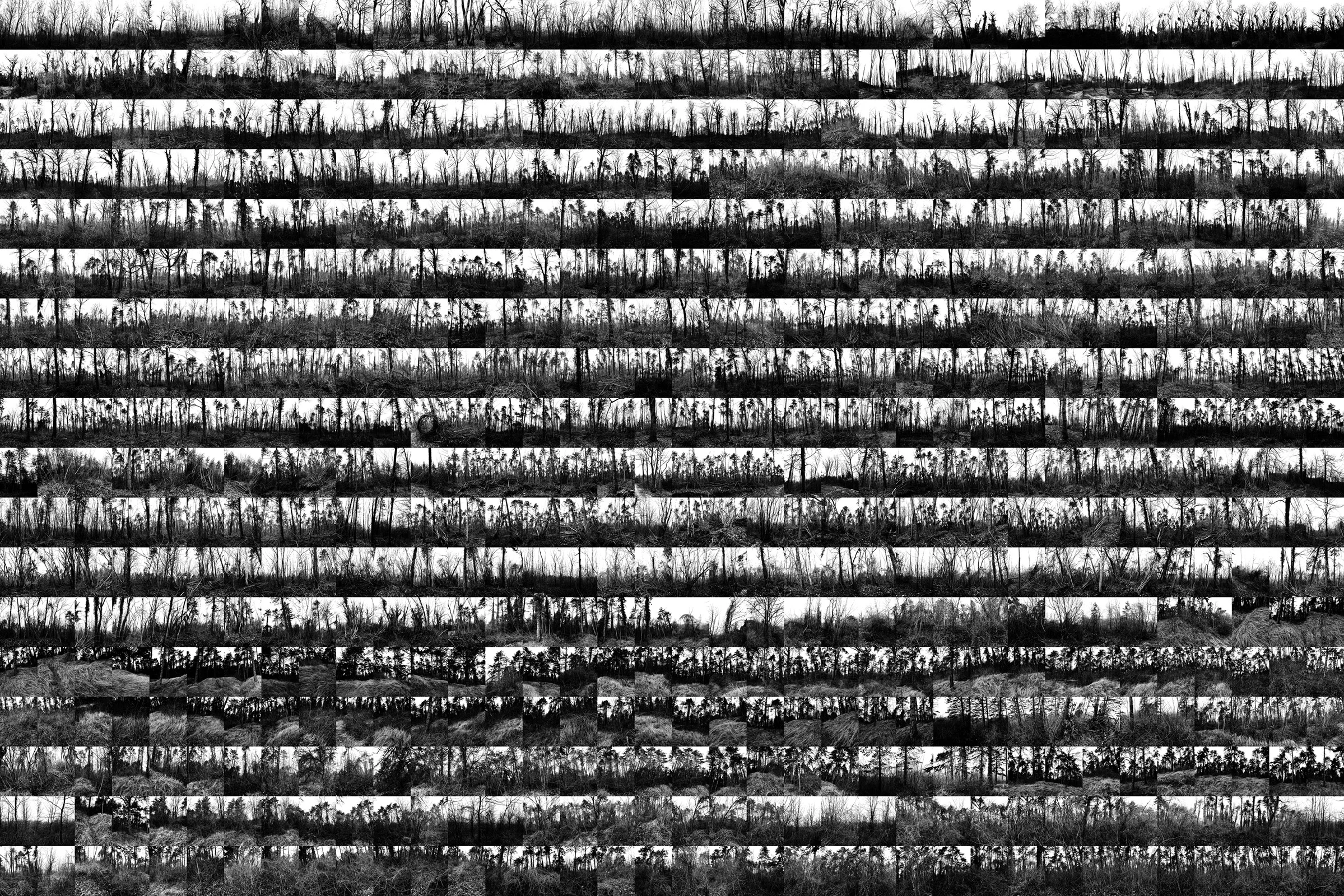

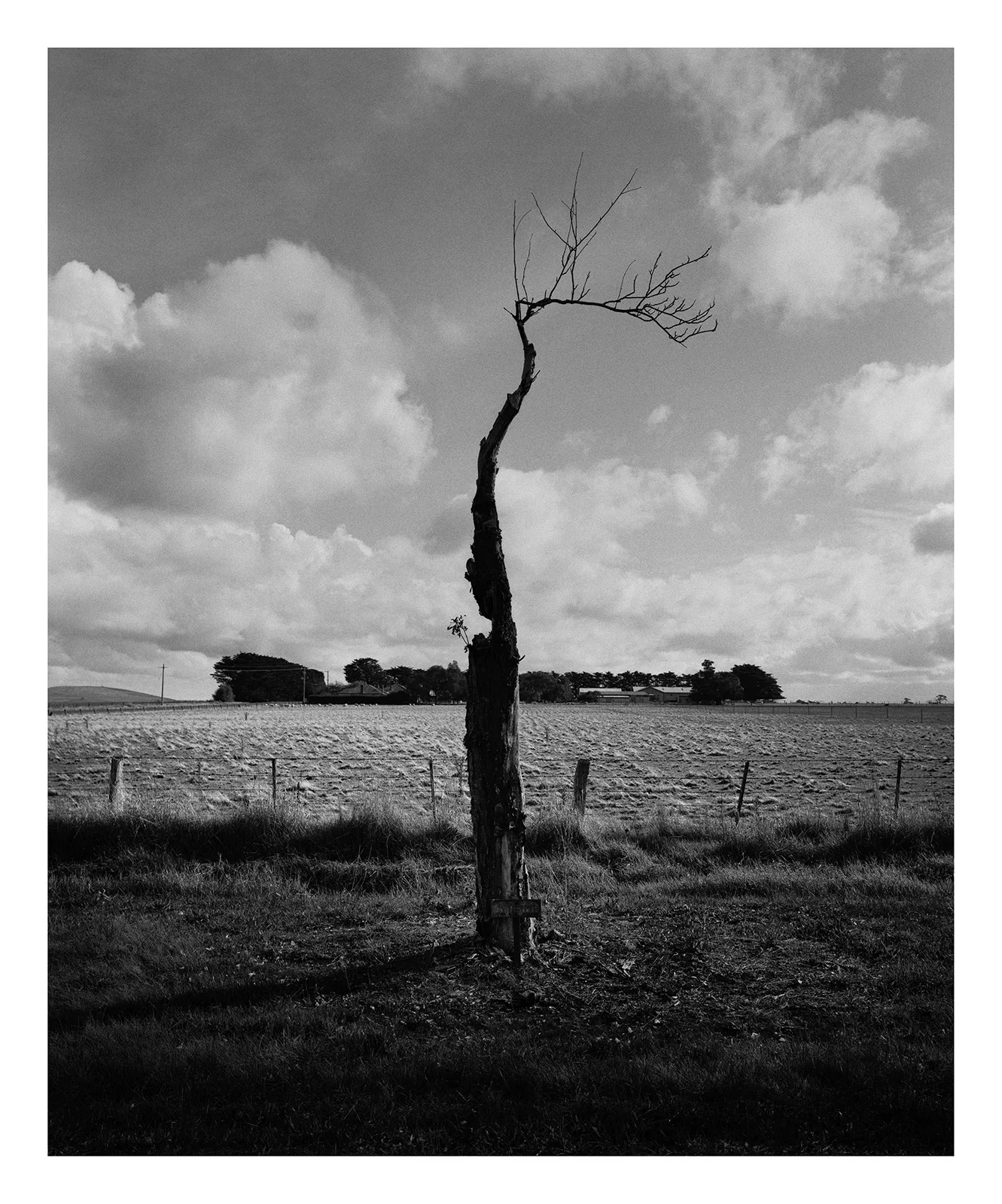

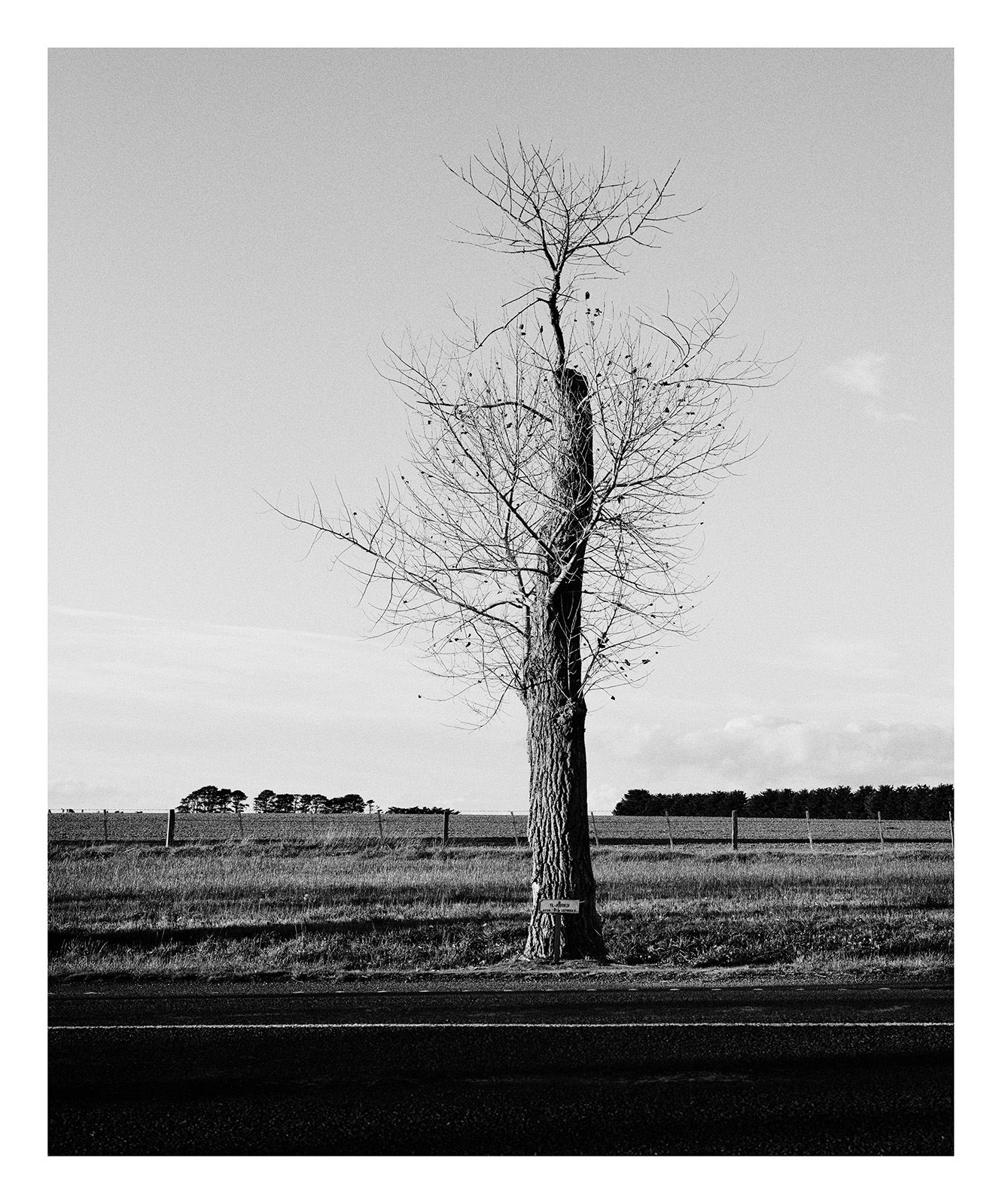

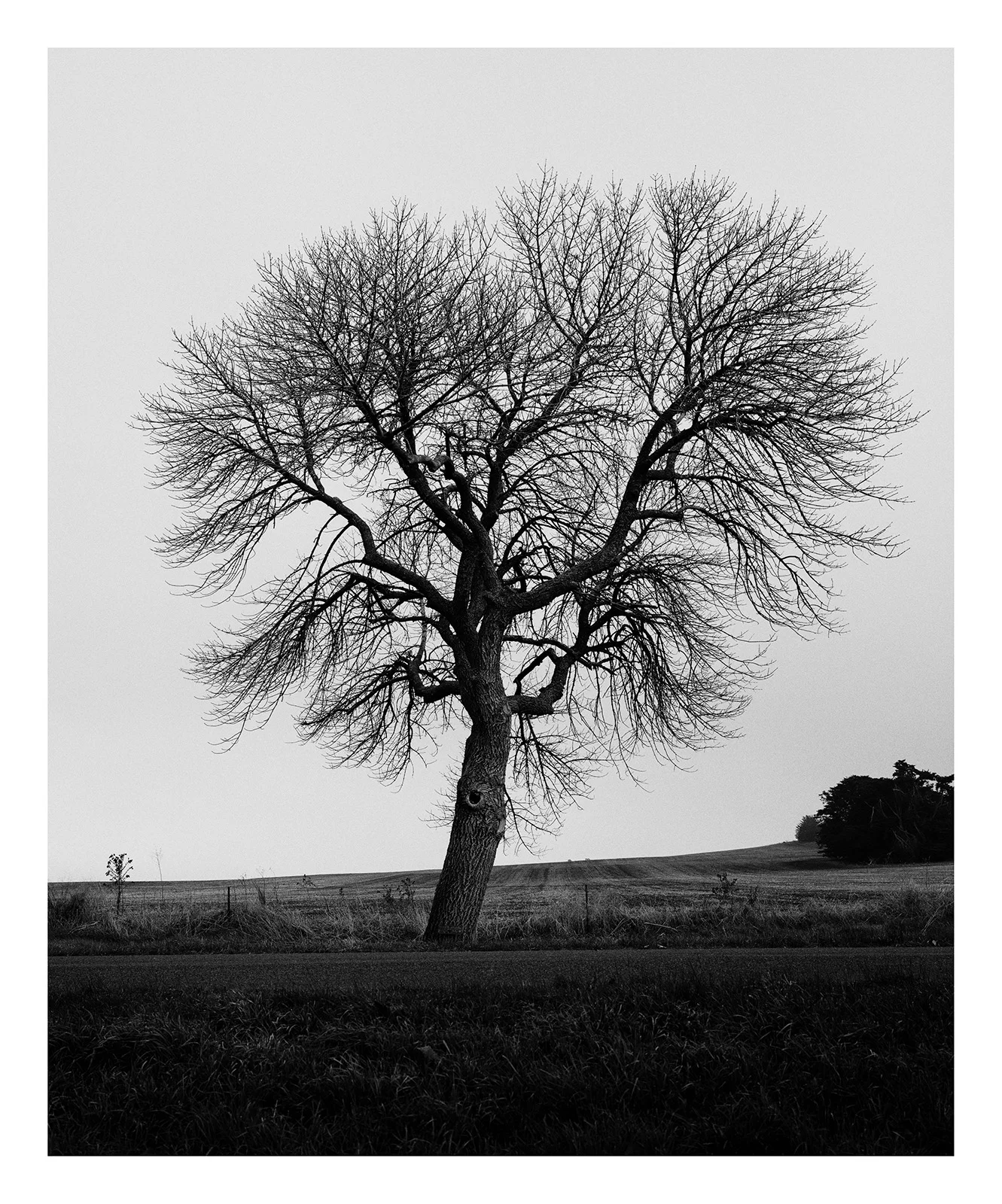

Trent Parke - The ballarat avenue of honour

More than 120 ‘avenues of honour’ were laid out during the great war in Australia, Trent Parke’s (1971) native country. Those left behind planted a tree for each local soldier sent to fight in Europe. The Ballarat Avenue of Honour was the first. It consists of 3,912 trees, which are still maintained and replaced today. ‘Almost 65% of Australian soldiers were killed — the highest proportion of any allied army. So the war was something very personal for Australians. I wanted to know how the landscape could bear witness to that.’